ADVERTISEMENT

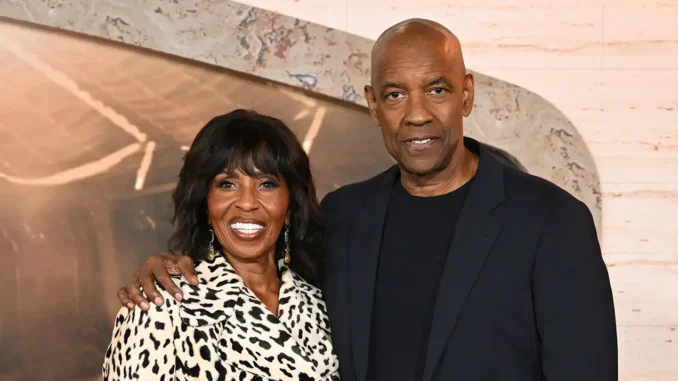

How Denzel Washington Found Freedom in Sobriety

A Hollywood Legend’s Journey from Two Bottles a Day to Ten Years of Freedom

By Emma Rodriguez | Source: Esquire Magazine Interview, November 2024

The wine cellar was magnificent—ten thousand bottles gleaming behind climate-controlled glass, each vintage representing years of patient aging, decades of craftsmanship. Château Margaux from 1961. Château Lafite Rothschild from 1982. Four-thousand-dollar bottles that most people would never dare open, arrayed like soldiers in formation, waiting. For Denzel Washington, that cellar wasn’t a collection. It was a prison with crystal walls.

“Wine is very tricky,” Washington revealed in a recent candid conversation with Esquire magazine. “It’s very slow. It ain’t like, boom, all of a sudden.”

The two-time Academy Award winner, approaching his 70th birthday this December, has spent the past decade walking a path few would have predicted for Hollywood royalty: the road of complete sobriety. But this wasn’t always his story.

The Seduction of Sophistication

It began innocently enough in 1999. Washington and his wife Pauletta had just built their dream home, complete with that spectacular wine cellar. What started as an appreciation for fine vintages—wine tastings, discussions of terroir and tannins—gradually evolved into something darker, more insistent.

“I learned to drink the best,” Washington explained. “So, I’m going to drink my ’61s and my ’82s and whatever we had. Wine was my thing, and now I was popping four-thousand-dollar bottles just because that’s what was left.”

The actor developed a ritual, calling Gil Turner’s Fine Wines & Spirits on Sunset Boulevard with the same request: “Send me two bottles, the best of this or that.”

His wife Pauletta would ask the obvious question: “Why do you keep ordering just two?”

Washington’s answer revealed the bargaining we all make with our demons: “Because if I order more, I’ll drink more. So I kept it to two bottles, and I would drink them both over the course of the day.”

Two bottles. Every day. For fifteen years.

The Performance Must Go On

Here’s where Washington’s story illuminates something Hollywood rarely discusses: functional addiction. The man who gave us Malcolm X, Training Day, Glory, and Flight never allowed his drinking to touch his professional work. He maintained an iron discipline on set, staying completely sober during filming.

“I never drank while I was working or preparing,” he emphasized. “I would clean up, go back to work—I could do both. However many months of shooting, bang, it’s time to go. Then, boom. Three months of wine, then time to go back to work.”

This pattern speaks to a larger truth about addiction in high-performing environments. As Jamie Lee Curtis once reflected on her own recovery journey: “Getting sober just exploded my life. Now, I have a much clearer sense of myself and what I can and can’t do.”

The cycle Washington described mirrors the experiences of countless celebrities who’ve walked similar paths. Bradley Cooper, who has been sober since 2004, told Barbara Walters something remarkably similar: “I would never be sitting with you, no way, no chance, if I hadn’t gotten sober.”

When Art Imitates Life

The intersection of Washington’s drinking and his art reached a powerful crescendo with the 2012 film “Flight,” where he portrayed Whip Whitaker, an alcoholic airline pilot who performs a miraculous crash landing while intoxicated. The role earned him an Academy Award nomination, but it also served as a mirror.

“I wasn’t drinking when we filmed ‘Flight,’ I know that, but I’m sure I did as soon as I finished,” Washington recalled. “That was getting toward the end of the drinking. But I knew a lot about waking up and looking around, not knowing what happened.”

The film’s director, Robert Zemeckis, had captured something authentic in Washington’s performance—that mixture of capability and chaos, the functional addict’s tightrope walk between brilliance and destruction. It wasn’t method acting. It was memory.

“I know during ‘Flight’ I was thinking about those who had been through addiction, and I wanted good to come out of that,” Washington said. “It wasn’t like it was therapeutic. Actually, maybe it was therapeutic. It had to have been.”

The Weight of History

Washington’s substance issues didn’t begin with wine cellars and vintages. They reached back to his youth in Mount Vernon, New York, hanging with his childhood friend Frank.

“To be honest, that is where it started,” he admitted. “I never got strung out on heroin. Never got strung out on coke. Never got strung out on hard drugs. I shot dope just like they shot dope, but I never got strung out.”

This early experimentation with harder substances never evolved into full-blown dependency, but it established patterns that would resurface decades later with alcohol. The demons we don’t address don’t disappear—they merely wait for different doors to open.

Daniel Radcliffe, reflecting on his own recovery journey, once observed something particularly relevant: “Addiction isn’t a choice; it’s something that happens to you.” It’s a perspective that Washington seems to have embraced in understanding his own story.

The Awakening at Sixty

Somewhere around his 60th birthday, Washington reached a crossroads. Perhaps it was the accumulating physical toll. Perhaps it was looking ahead at the years remaining and deciding what kind of legacy he wanted to leave. Perhaps it was simply grace.

“I’ve done a lot of damage to the body,” Washington acknowledged with characteristic directness. “We’ll see. I’ve been clean. Be ten years this December. I stopped at sixty and I haven’t had a thimble’s worth since.”

A thimble’s worth. Not a sip, not a taste, not even that. Complete abstinence, the kind that requires daily commitment and constant vigilance.

“Things are opening up for me now—like being seventy,” he reflected. “It’s real. And it’s okay. This is the last chapter—if I get another thirty, what do I want to do? My mother made it to ninety-seven.”

This framing—”the last chapter”—echoes Drew Barrymore’s hard-won wisdom: “Life is very interesting… in the end, some of your greatest pains become your greatest strengths.”

The Brotherhood of Recovery

Washington’s transformation extends beyond simply not drinking. About two years ago, his friend and “little brother” Lenny Kravitz introduced him to a personal trainer who is also “a man of God.” The connection speaks to something recovery specialists emphasize: sustainable sobriety rarely happens in isolation.

“I started with him February of last year,” Washington shared. “He makes the meals for me and we’re training, and I’m now 190-something pounds on my way to 185. I was looking at pictures of myself and Pauletta at the Academy Awards for ‘Macbeth,’ and I’m just looking fat, with this dyed hair, and I said, ‘Those days are over, man.’ I feel like I’m getting strong. Strong is important.”

The emphasis on strength—physical, mental, spiritual—mirrors the approach that’s sustained other celebrities in recovery. Rob Lowe, who has decades of sobriety, once said: “I’m under no illusions where I would be without the gift of alcoholism and the chance to recover from it.”

Bradley Cooper has similarly emphasized the role of community, having supported both Robert Downey Jr. and Ben Affleck on their recovery journeys. As Cooper observed about sobriety: “Getting sober was one of the three pivotal events in my life, along with becoming an actor and having a child. Of the three, finding my sobriety was the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”

Hollywood’s Hidden Epidemic

Washington’s public acknowledgment of his struggles adds his voice to a growing chorus of industry professionals who are pulling back the curtain on addiction in entertainment. The pressure, the access, the endless celebrations where champagne flows like water—these elements create a perfect storm for substance dependency.

Robert Downey Jr., whose comeback from addiction and incarceration to become one of Hollywood’s highest-paid actors stands as one of cinema’s great redemption stories, has spoken about how addiction nearly destroyed everything. “I have made many mistakes in my life, but each day is a chance to start again,” he reflected.

Colin Farrell, another actor who’s been open about his recovery journey, told Details Magazine: “I’m grateful that I’m actually alive. I have eight hours a day now that I didn’t have before, when I was drinking every day for eighteen years.”

Edie Falco, whose portrayal of the addiction-struggling Nurse Jackie drew from her own recovery experience, offered another perspective: “It’s like learning to ride a bike, you know? You have to get your bearings and you have to stay stable.”

These aren’t isolated incidents. They’re symptoms of an industry where success and excess often intertwine, where the line between celebration and destruction blurs in the golden light of achievement.

The Moral Architecture of Recovery

What makes Washington’s story particularly compelling isn’t just that he struggled—it’s how he framed his recovery. His reference to “the last chapter” suggests a man thinking deeply about legacy, about what remains after the awards are given and the films fade from memory.

In an industry that often celebrates youth and novelty, Washington is modeling something different: the wisdom that comes from confronting one’s demons and choosing a different path. His transparency about the “damage” done to his body represents a form of accountability rarely seen from figures of his stature.

As Russell Brand, who has also been vocal about his recovery, observed: “The only way to change is to change your behavior every day.” It’s this daily commitment—the decision renewed each morning not to pick up that first drink—that separates sustained recovery from temporary sobriety.

Eric Clapton, reflecting on decades of recovery from his own substance issues, offered another crucial insight: “My identity shifted when I got into recovery. That’s who I am now, and it actually gives me greater pleasure to have that identity than to be a musician or anything else, because it keeps me a manageable size.”

The Cost of Excellence

Washington’s story also raises uncomfortable questions about how we celebrate excellence. Those ten thousand bottles weren’t just alcohol—they were status symbols, markers of sophistication and success. The wine cellar itself was an architectural achievement, a temple to refined taste.

But as Washington discovered, refinement can be its own trap. The slow seduction of “fine living” can be more dangerous than obvious excess because it comes wrapped in cultural approval. Nobody stages an intervention for the sommelier discussing vintage classifications while systematically drinking two bottles a day.

This is what makes wine particularly “tricky,” as Washington noted. It’s socially acceptable, culturally elevated, and seamlessly integrated into professional life and celebrations. The bottles Washington was opening—those 1961 Bordeaux, those 1982 Château Margaux—weren’t seen as warning signs. They were seen as evidence of his success.

Breaking the Silence

By speaking openly with Esquire about his decade of sobriety, Washington joins a tradition of celebrities using their platforms to destigmatize addiction and recovery. His honesty serves multiple purposes: it offers hope to those still struggling, it provides perspective to those in early recovery, and it challenges the silence that often surrounds addiction in successful communities.

Demi Lovato, who has been remarkably open about recovery struggles, once said: “My message is that there is hope in recovery, and you can have a healthy, fulfilling life without drugs or alcohol.” It’s a message amplified when delivered by someone of Washington’s stature and reputation.

Jamie Lee Curtis has called her recovery “my single greatest accomplishment, bigger than my husband, bigger than both of my children, and bigger than any work, success, failure. Anything.” The primacy she places on sobriety over all other achievements speaks to how fundamental the transformation is.

The Road Ahead

As Washington approaches 70, he’s thinking about endings and beginnings. He’s hinted that “Gladiator II” and potential future projects like “Black Panther 3” might be among his final films. But more importantly, he’s thinking about how to spend whatever years remain.

“This is the last chapter—if I get another thirty, what do I want to do?” he asked. It’s a question that reflects hard-won clarity, the kind that only comes from staring down one’s mortality and choosing life.

His reference to his mother reaching 97 isn’t just about longevity—it’s about quality. About being present for grandchildren. About mornings without regret. About the strength to stand, clear-eyed and honest, before whatever comes next.

As Ben Affleck, who has publicly struggled with alcohol addiction and multiple rehab stays, observed: “If you have a problem, getting help is a sign of courage, not weakness or failure.” Washington’s decade of sobriety represents that courage sustained over thousands of days, each one a small victory, each one a choice.

The Gift of the Last Chapter

Perhaps the most powerful aspect of Washington’s story is his framing of this period as “the last chapter”—not an ending, but a completion. He’s not mourning what’s behind him; he’s clear-eyed about what’s ahead.

This perspective echoes something Anthony Hopkins, who has nearly 50 years of sobriety, once said about recovery: “You have to want to change. You have to use your pain as fuel to make a better life for yourself.”

Washington has done exactly that. He’s taken the pain of addiction, the damage to his body, the wasted days in wine-induced hazes, and alchemized them into something else: a legacy of honesty, a model of recovery, and a roadmap for others who might be building their own ten-thousand-bottle cellars, one sophisticated prison bar at a time.

As he told Esquire with characteristic directness: “I feel like I’m getting strong. Strong is important.”

Not successful. Not celebrated. Not even sober, though that’s the foundation of everything else.

Strong

In the end, that might be the greatest performance Denzel Washington ever gives—not as Malcolm X or Whip Whitaker or Easy Rawlins, but as himself, ten years sober, approaching 70, looking back at the wreckage and forward at the possibility, and choosing strength over comfort, honesty over image, life over the slow, tricky seduction of wine.

His mother made it to 97. With this last chapter written the way he’s writing it—one sober day at a time—there’s every reason to believe he might just match her.

—

Emma Rodriguez is a features writer specializing in entertainment, culture, and recovery narratives. Her work has appeared in various publications covering the intersection of celebrity, mental health, and personal transformation.

ADVERTISEMENT

Primary Source: Esquire Magazine Interview with Denzel Washington, November 2024

Leave a Reply